Hover over the painting to magnify (there may be an initial delay while the magnified image is loaded)

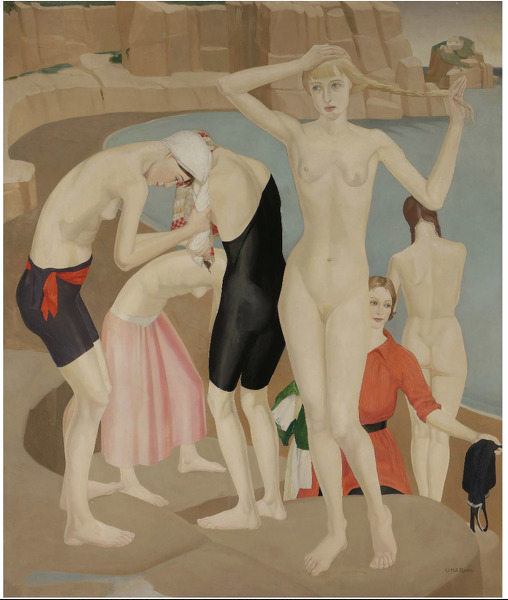

Hover over the painting to magnify (there may be an initial delay while the magnified image is loaded)Gladys Hynes (1888-1958):

Morning, c.1915

Framed (ref: 10562)

Signed,

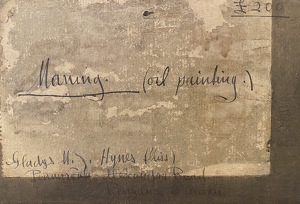

Oil on panel, two labels to the reverse, inscribed

Morning (oil painting) – Gladys M. J. HYNES (Miss) -

Penmorvah, Alexandra Road in Penzance, Cornwall –

200 £ - number 39330.

46.1 x 38.6 in. (117 x 98 cm)

See all works by Gladys Hynes oil panel tempera allegory big pictures design leisure seascapes and skyscapes sport TOP 100 women 1.PORTRAIT OF AN ARTIST 49 pictures Rediscovering Women Artist Hidden Gems - Nudes

Provenance: Collection Oscar Ghez circa 1960 for Petit Palais (Genève), until 2019

Literature: Llewellyn, Sacha, and Paul Liss. Portrait of an Artist. Liss Llewellyn, 2021, p.351.

Morning is a previously unrecorded work by Gladys Hynes (1888 – 1958) which belongs to a series of paintings produced in the 1910s in which Lamorna Cove (West Cornwall) forms the backdrop. The beauty spot, a favourite haunt of the Newlyn artists, is especially associated with Laura Knight who lived in Lamorna Valley and painted a celebrated series of compositions of figures posed on the cliffs.

(Laura Knight, On the Cliffs, circa 1917)

In her autobiography Oil Paint and Grease Paint (1936) Knight described how the ‘cliffs, rocks and sea were fine to paint with figures bathing and swimming in the pools or dressing and undressing’. Hynes, who lived in West Cornwall between 1906 and 1919, recalled how she loved to lie on the cliffs all day looking out to sea, which was ‘as smooth and glittering as a dancing floor…and lovely as a dream’.

(Gladys Hynes, Chalk Quarries, 1917)

Stylistically, Morning can be situated between Hynes picture In the Park, (1912), a conscious attempt to paint in the contemporary Post-Impressionist idiom, and Chalk Quarries (1917), in which emphasis is given to the underlying geometry. In Morning, the arrangement of the bathers is carefully controlled and choreographed while the rendering of the shoreline is schematic and static, the sense of atmosphere, space and spontaneity surrendered to flat bands of colour. Indeed, C. E. Vulliamy, Hynes’ fellow student at the Newlyn School, noted her interest in Cubism, describing her paintings as ‘stylisations of characteristic form’. This heightened sense of design also underscored Hynes’ later masterpiece, Noah’s Ark (1919), one of the highlights of the Daily Express’s ‘Young Artists Exhibition’ held at the Royal Society of British Artists in 1927.

(Gladys Hynes, Noah's Ark, 1919)

While in Morning Hynes demonstrates an awareness of the grande baigneuses of the Impressionists and Post-impressionists (including Renoir, Gaugin, Monet and Cézanne), the artist she seems closest to in spirit is Seurat, whose work influenced other Newlyn artists, most notably Dod Procter. As well as sharing the same colour palette (pinks, burnt orange, black, red and fawn) of Seurat’s Bathers at Asnières (1884), Morning also mirrors the sense of timeless melancholia and composed grandeur of Seurat’s painting. Hynes’ Morning also evokes a dialogue with Piero della Francesca, especially in the young woman in pink, the smooth curve of her bowed back echoing the figure disrobing for baptism in Piero’s Baptism of Christ (1448-50).

(Georges Seurat, Bathers at Asnières, 1884)

For her models, Hynes called on her artist friends. The figure drying her hair can be identified as Dod Procter, who also lived in Newlyn, while the fully clothed figure in orange is Nina Hamnett, with whom Hynes had developed a deep friendship when they were students at Brangwyn’s London School of Art. ‘I keep remembering the brilliantly gay and very talented creature-and one of the most shapely our creator ever produced’, Hynes would write on Hamnett’s death in 1956. The central nude bears a striking resemblance to Hynes herself; in ambitious figure compositions it was not unusual for artists to include themselves as the central protagonist, as in Winifred Knights The Deluge (1920).

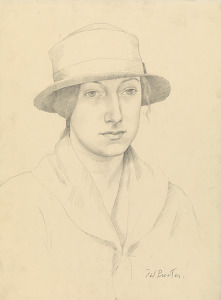

(Dod Proctor, Portrait of Gladys Hynes, circa 1919)

It is likely that Hynes painted Morning in the tranquility of her Newlyn studio, as by 1915 The Defence of the Realm Act (DORA), which prevented artists from working out of doors, was being strictly enforced in Cornwall, for it was there that a German invasion was most feared. Alfred Munnings, who lived at Lamorna, remarked that he 'dared not be sketching out of doors in the country at all'

While the first generation of Newlyn painters typically portrayed the Cornish coastline as a place of daily toil (see for example Stanhope Forbes Fish Sale on a Cornish Beach (1885)), Morning, in common with Laura Knight’s compositions, intersects closely with the modern culture of the beach as a place for leisure and contemplation. The six women have emerged revived from an early morning swim, and yet a pensive air seems to float around them. While at first sight Morning can be read as a form of hymn to the joys of sea bathing, Hynes was painting the composition at a time when the nation was in the midst of the First World War. This would prove to be an agonizing period of loss for Hynes; her brother Patrick was killed in 1915 in a plane crash while her brother Hugh would suffer from the effects of shellshock for many years to come. Typical of an iconography that would increasingly characterize Hynes’ work, Morning thus challenges the viewer to look beyond the fantasies of a traditional idyll to a more contemporary (and often darker) reality. As the critic Charles Marriot wrote in 1917, despite the ‘decorative treatment’ of Hynes’ paintings, they had ‘the bite of life, and of modern life’ which produced ‘an effect of deliberate awkwardness’. The men who are, on second glance, absent from the tranquil scene, may not return to their native coast. Likewise, Hynes was soon to leave behind Cornwall’s gentle pattern of life, at first during wartime commutes to London to join Roger Fry’s Omega Workshops and in 1919 to set up her studio permanently in London where she would embark on the next stage of her remarkable career.

British Post-Impressionism

British Post-Impressionism Privately held

Privately held